In my last post, I tried to show how energy loops can transfer heat energy around a building, a network, or even a whole community and hopefully I demonstrated the advantages to society if we all maximise their use to save energy and reduce carbon emissions.

Now, I’d like to focus on how different technologies can work together in an energy loop to give carbon footprint savings, cut operational costs and allow a building to benefit from government incentives.

You may be surprised by a heat pump manufacturer talking about other people’s products but one thing I’ve learnt during my time at Mitsubishi Electric is that we first and foremost want to give people information so that whatever their requirements, they have all of the data necessary to make an informed decision.

So this month, I want to point to a live example of a CHP (Combined Heat & Power) system working in tandem with some of our heat pumps.

We've been working closely with SAV Systems on connecting their LoadTracker CHP systems with our Ecodan heat pumps.

SAV Systems are leaders in low carbon technologies and energy efficient heating systems and LoadTracker CHP systems are already installed in schools, hospitals, community centres, offices and other buildings throughout the UK. In fact, CHP systems are suited to almost any site that requires electricity and heat, so the potential sector is vast.

This combination of low carbon and renewable energy can offer a powerful solution and the concept is tried and tested in many Danish installations.

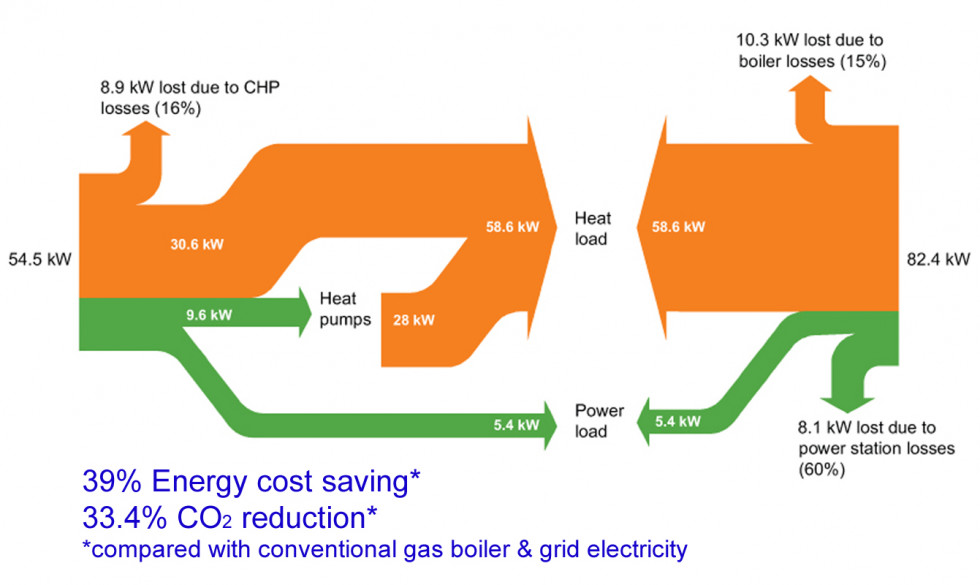

Combining electric air source heat pumps with CHP can significantly increase the share of low carbon heat, particularly when the project has a comparatively low electrical demand for the CHP. This is often the case in schools and ‘landlord’ areas within multi-residential developments.

As electricity consumers, heat pumps create additional electrical load for on-site CHP generation. Heat pumps can be activated during periods of reduced power consumption; for example, by topping-up low night-time electrical loads.

This combination of low carbon and renewable energy can offer a powerful solution and the concept is tried and tested in many Danish installations.

SAV have also produced a case study under the title ‘How to Optimise SAP/SBEM CHP Heat Share with Heat Pump’ which focuses on a school campus expansion project in Witney, Oxford.

The project provided additional space to accommodate both upper and lower school pupils at the same campus, and SAV had to meet the challenge of achieving a CO2 reduction through on-site energy generation. At the same time, the solution had to satisfy ‘Part L’ and SBEM while minimising project costs and payback time.

CHP and Air Source Heat Pumps combine to supply the high and low-temperature circuits in the school, which benefits from a lower carbon footprint, operational cost savings – and an RHI compliant ASHP installation.

The Heat Pump provides a steady electric load for the CHP, increasing the available operating hours, maximising the heat share and reducing electricity export.

Richard Venga is Central Plant Sales Engineer at Mitsubishi Electric.

If you have any questions about this article or want to know more, please email us. We will contact the author and will get back to you as soon as we can.